Copyright Notice: We don't think much of copyright, so you can do what you want with the content on this blog. Of

course we

are hungry

for publicity, so we would be pleased if you avoided plagiarism and gave us credit for what we have written. We

encourage you not to impose copyright restrictions on your "derivative" works, but we won't try to stop you. For the legally or statist minded,

you can consider yourself subject to a Creative Commons Attribution License. |

|

In the previous post, we saw that the dramatic increase in patent awards since about 1980 has not been accompanied by any consequent change in overall economic growth in the United States. But before we conclude that patents don't do anything at all (except employ examiners and attorneys), let's look a bit farther afield.

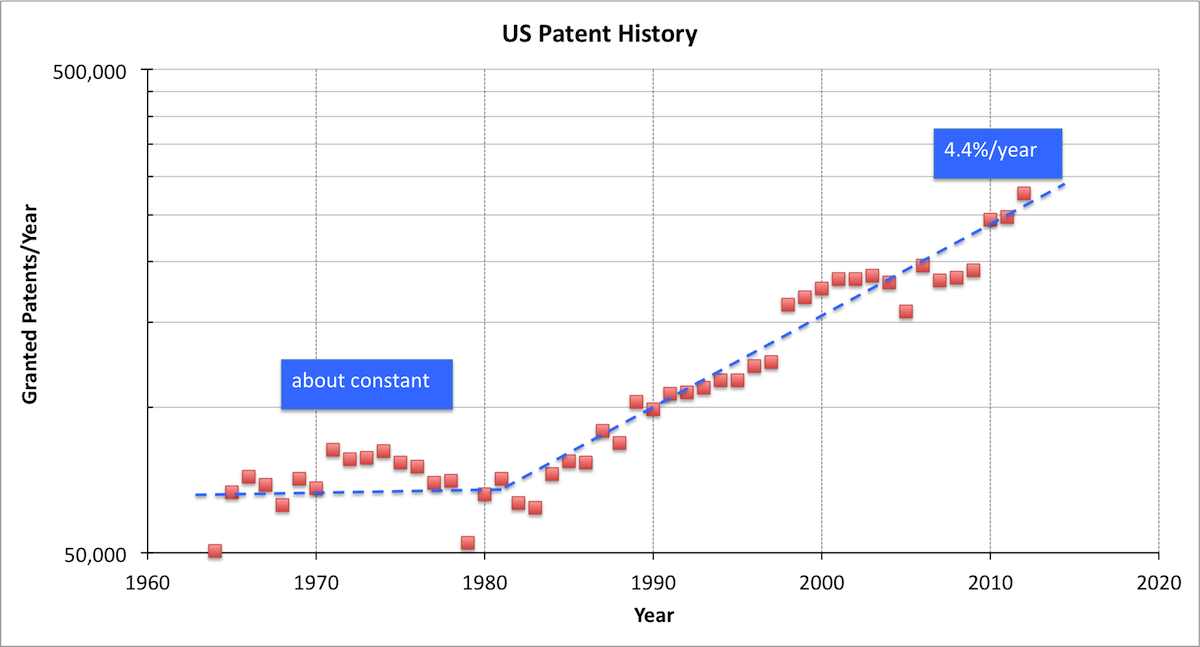

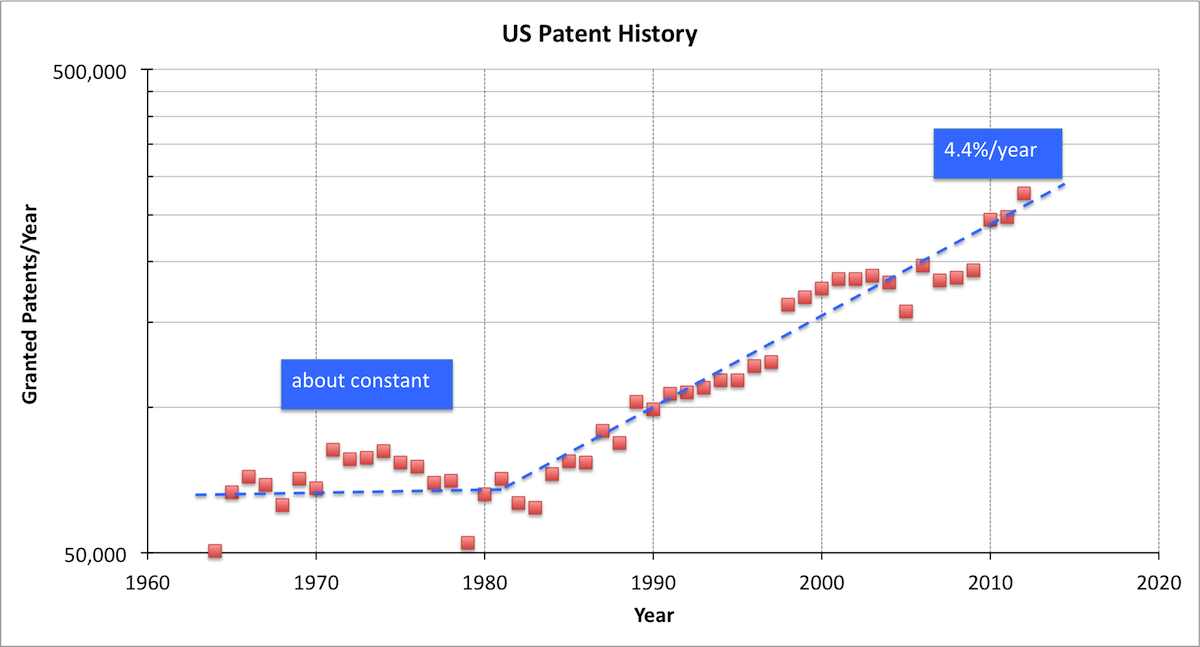

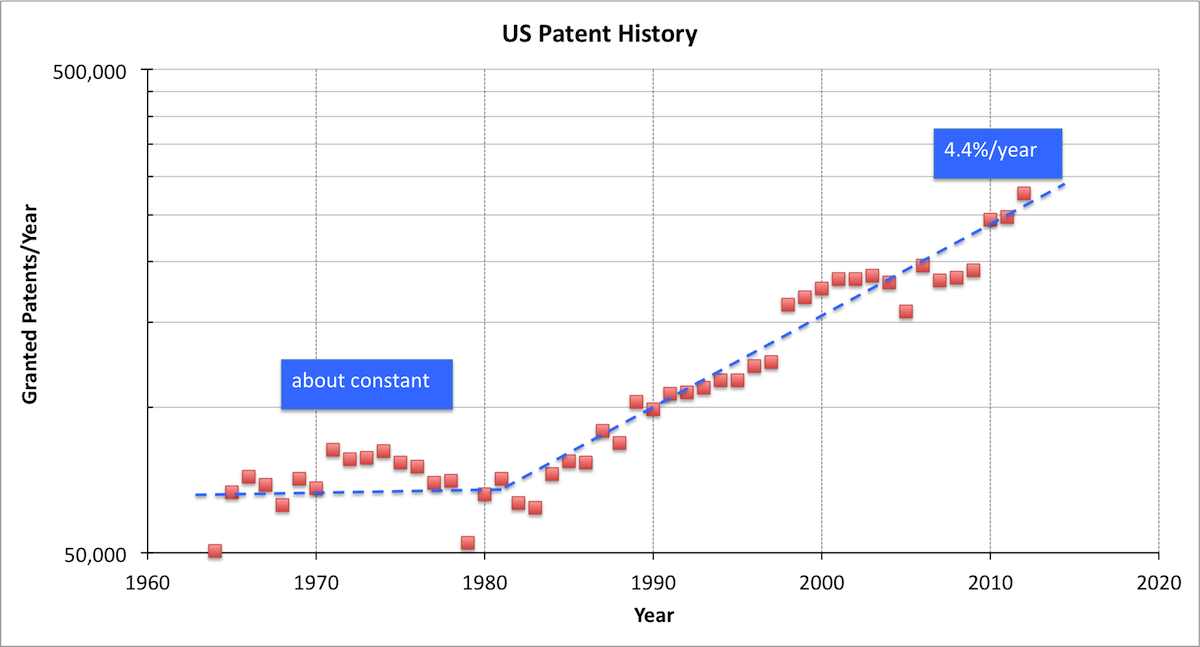

For convenience, we repeat below the diagram shown in the previous post, of annual patent grants for the last half-century plotted on a logarithmic scale.

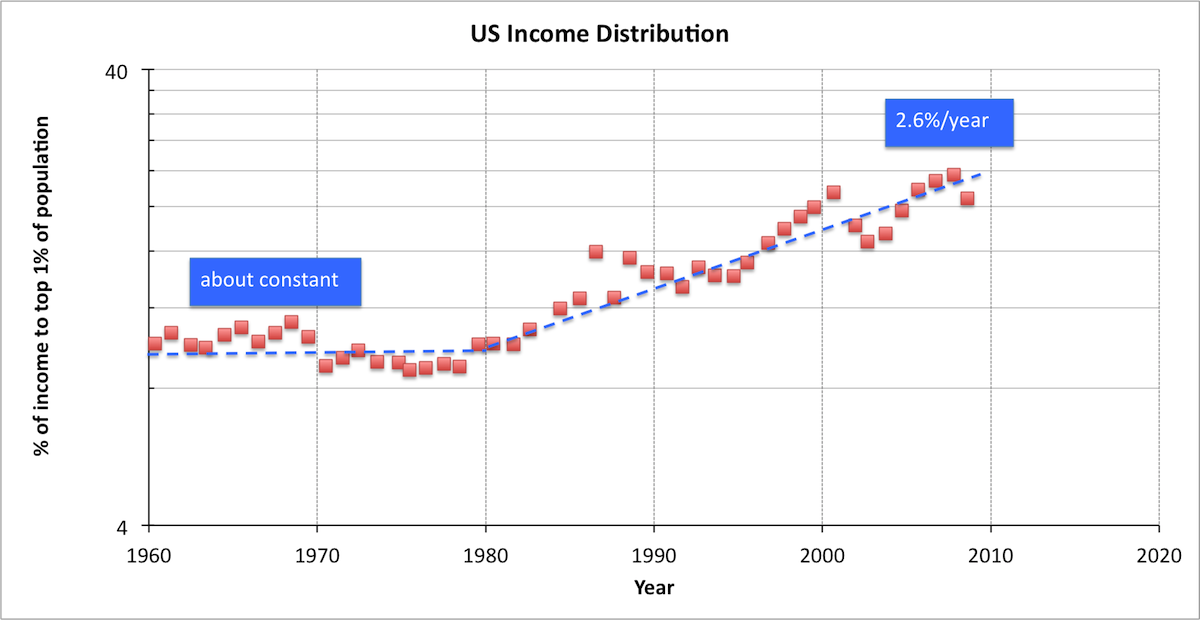

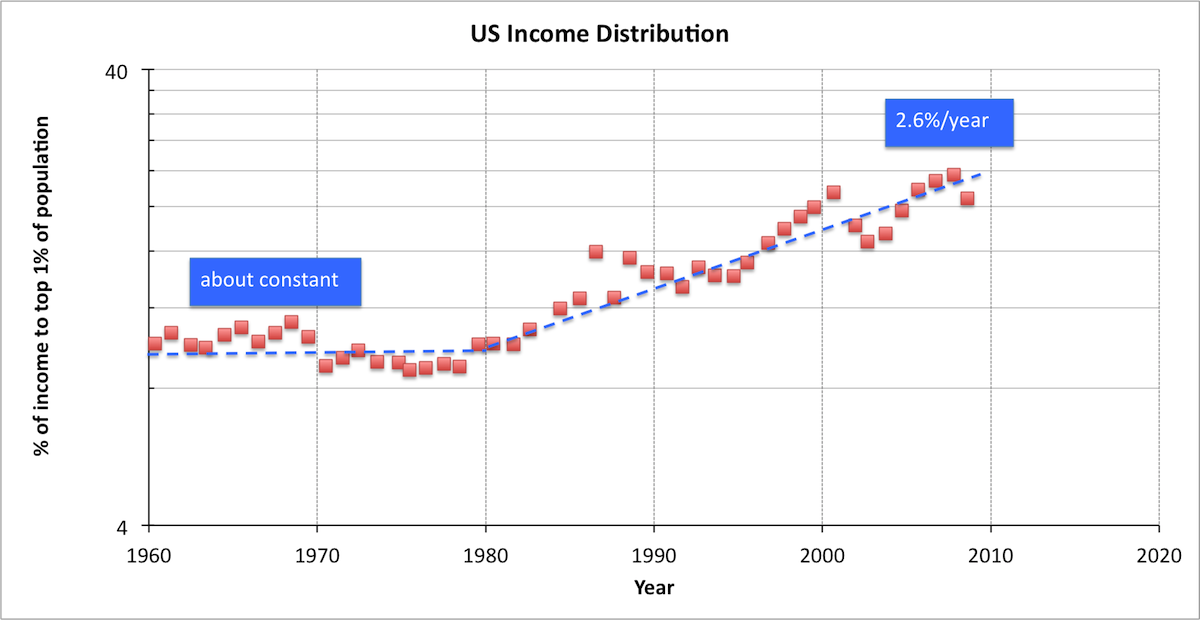

In the next graph, using data from Thomas Piketty's remarkable work Capital in the 21st Century, we plot the percentage of US national income collected by the top 1% of earners for about the same time period:

We can immediately see that, just like the number of patent grants, the share of income going to the top centile was about constant (or perhaps falling a bit) in the period 1960 to 1980, and then some time between 1980 and 1983 started going up dramatically. While there's a lot of scatter, we can make a plausible approximation that the share grows at about 2.6%/year from 1980 to 2010. This isn't exactly the same as the rate of growth of patent grants, but it isn't that different. Certainly the qualitative behavior of the two datasets is extremely similar. It's not easy to say if one is delayed with respect to the other, so the relationship might be causal, or it might be that both are the result of a single common cause. (Or, of course, the correlation could be accidental.) But in any case, this dataset looks a lot more like something related to patenting than the US GDP did.

Now, folks who have studied these issues (such as Prof. Piketty) would point at changes in tax law and corporate culture long before looking at intellectual property issues, when searching for the reasons behind the increase in wealth concentration in recent decades. And quantitatively they are probably correct. If we value each patent granted at $50,000, then the total value of a year's patenting is around twelve billion dollars. Even if that's pessimistic by a factor of 3 or 4, it's still a rather tiny fraction of the US GDP of around fifteen trillion dollars today. It seems reasonable that we should regard the close resemblance of our two graphs as showing that the behavior of both datasets is driven by a common cause, which we might characterize as the increasing influence of established wealth in governmental policy over the last 3 decades.

Nevertheless, we will suggest by the following argument that the result we see is consistent with a sensible understanding of what granting lots of patents might be expected to produce. A patent is a right to exclude: it gives the holder the legal right to prevent other people or organizations from doing something that, absent the patent, they have the ability and resources to accomplish. (You can't sue someone for infringement unless they are able to infringe.) About 90% of granted patents are owned by corporations, in the majority of cases due to compulsory assignment as a condition of employment. This percentage, incidentally, was only 71% in 1991.

The possession of these rights would be expected to have two consequences. The first is that the relative value of an employee relative to an employer is reduced: the employer now owns something the employee knows how to do. The employee can make improvements on an invention, possibly for a different employer, and patent same - but if the practice is still covered by the first grant, the initial employer can exclude the inventor from their own invention.

The second consequence is that established firms can raise barriers to entry by owning large numbers of patents. Barriers to entry increase profitability by reducing the number of competitors in a space without the need for product improvements. As noted, for example, by Boldrin and Levine in Against Intellectual Monopoly, patenting tends to increase as industries mature. Exclusion of competitors without corresponding improvements in products or services represents a net transfer of wealth to corporate management and investors over consumers. If patents were granted only for substantial improvements in products or services, and thus their disclosure represented a public good, it is possible that this transfer might be mitigated by the benefit to the public. However, US patents are in fact granted more or less at random, with little distinction between meaningless and profound disclosures. (We will discuss this assertion in more detail in the next post; a similar point is made in a recent post from the folks at Patent Progress: Why We Need Better Patent Quality.) It is unlikely that the resulting public benefit would outweigh the cost of granted rights to exclude.

And, of course, the third consequence of granting rights to exclude is the rise of non-practicing entities, patent "trolls", whose activities involve no products at all, but simply the threat of exclusion of other parties as a means of extorting payment.

Thus, it is plausible, though hardly proven, that the increase in US patenting has played a role in the roughly contemporaneous increase in the concentration of wealth in the United States. Research work in the islands of the Aegean sea over 2300 years ago, reported in Will Durant's The Life of Greece [1], showed that a substantial middle class is required for the success of a democratic system of government. While many other changes in policy are needed to moderate and perhaps reverse the progress of the United States towards a plutocracy, improvements in the means of granting patent monopolies can play a role. Suggestions for such improvements - some modest, some wildly ambitious - will constitute the topics of the remainder of this series of posts.

Sources:

USPTO; Capital in the 21st Century, T. Piketty (trans. A. Goldhammer), figure 8.6; http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/seind93/chap6/doc/6e1a93.htm; http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/14/opinion/my-ideas-my-bosss-property.html;

Notes:

1: OK, I'm doing this one from memory; my copy is buried in the garage, don't ask. If someone has a digitized version of the book and can provide the specific citation (and any corrections to my instant characterization) I'd appreciate the help.

[Posted at 09/28/2014 10:13 AM by Daniel Dobkin on IP and Economics  comments(0)] comments(0)] Patents and Economic Growth: A Beautiful Experiment

Any time someone proposes changes in the patent system, they can expect to encounter platitudes about how important the protection of "intellectual property" (a term invented in the 1970's) is to innovation and prosperity. Just about everyone involved in the system seems to accept the notion that patents are important in promoting technological progress and thus economic growth. For example, in testimony to the US Congress last year, former USPTO director David Kappos, referring to patent reforms, said "…we are reworking the greatest innovation engine the world has ever known." But people believe a lot of things that aren't true. Is this one of them?

It turns out that, courtesy mostly of the Federal courts with just a bit of help from Congress, the United States has performed a lovely experiment in the last five decades that conclusively demonstrates that patents do not play a role in promoting the overall economy. Let's take a look.

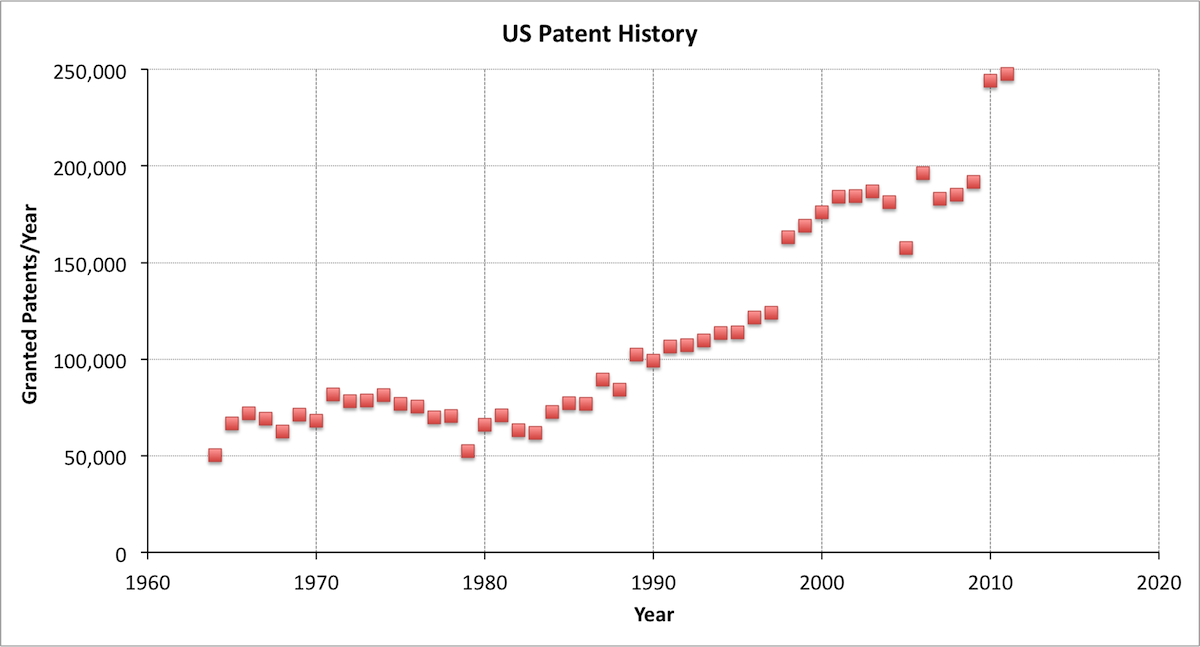

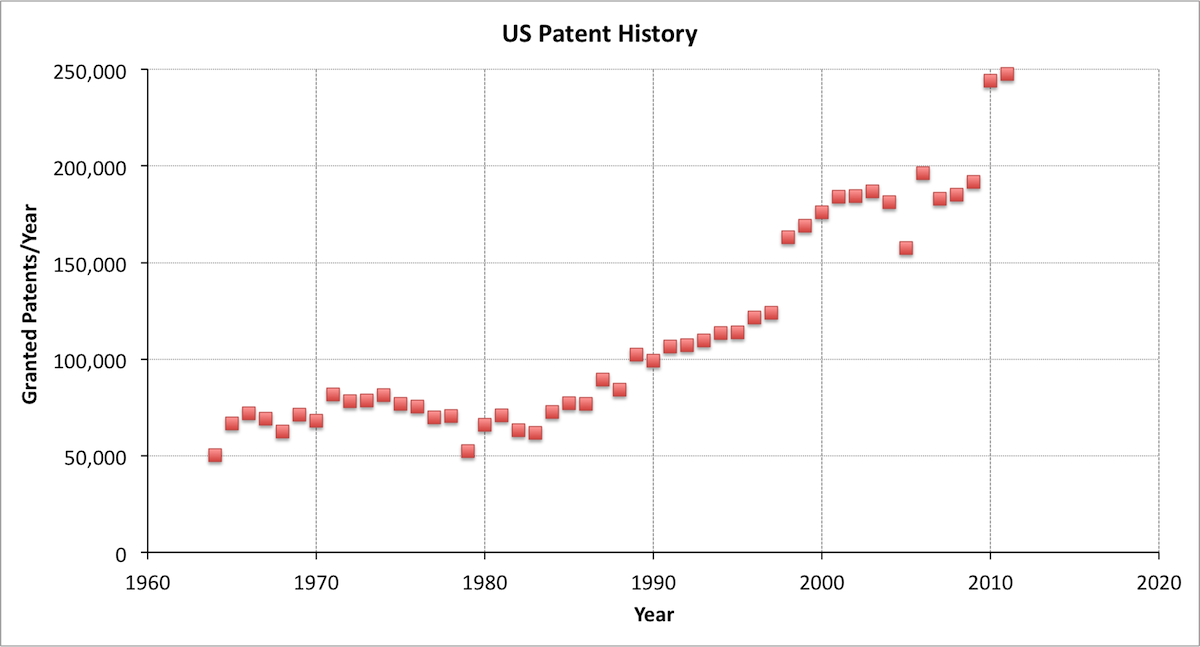

The figure below shows the number of patents granted per year, from the early 1960's until last year.

We can immediately see that the number of patents granted per year was about constant for quite a long time, from roughly 1962 to 1982, but then increased dramatically (and is still going up). By the end of the period, about four times as many patents were being granted per year as at the beginning. If patents are important for economic growth, we would expect to see some sort of secular increase in growth corresponding to this massive change in patenting. And on the contrary, if patents are detrimental to growth, we'd expect to see growth decrease starting around the 1980's. Naturally, we wouldn't be surprised if the response to this change was delayed a bit, as the effects of patent grants might take a while to percolate through the system. However, the changes can't be delayed by more than the 17- or 20-year term of a patent, and it's been more than 20 years since the changes started. This is as nice an experiment as you get to do in the social sciences, so whatever result we get has to be considered as authoritative.

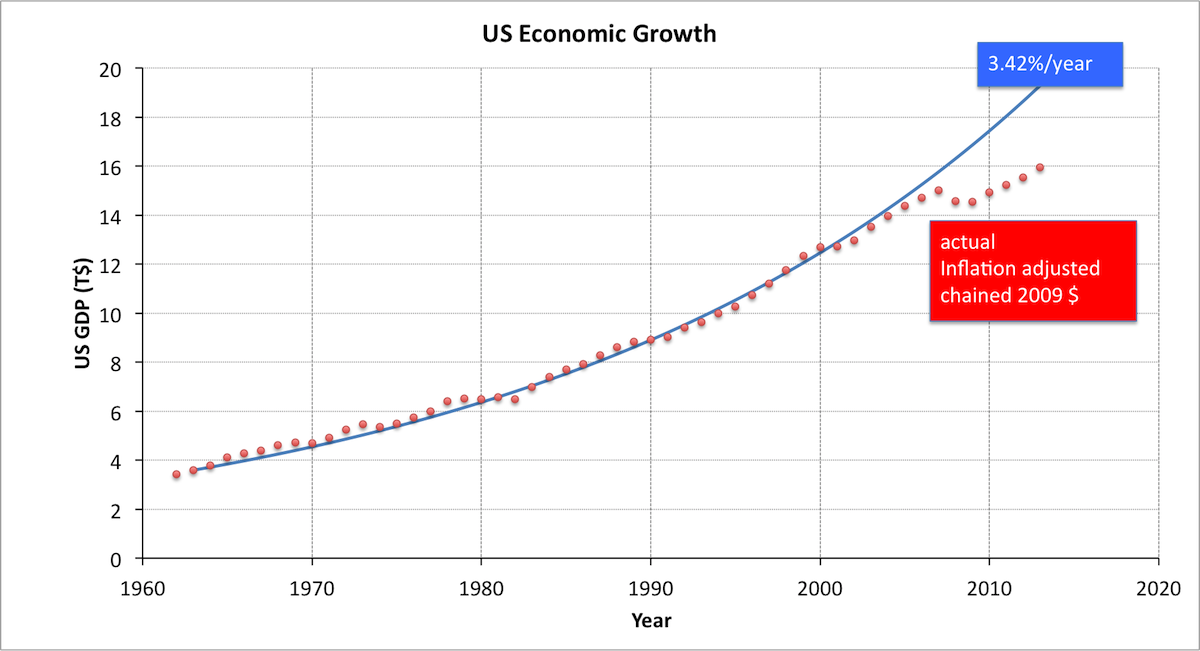

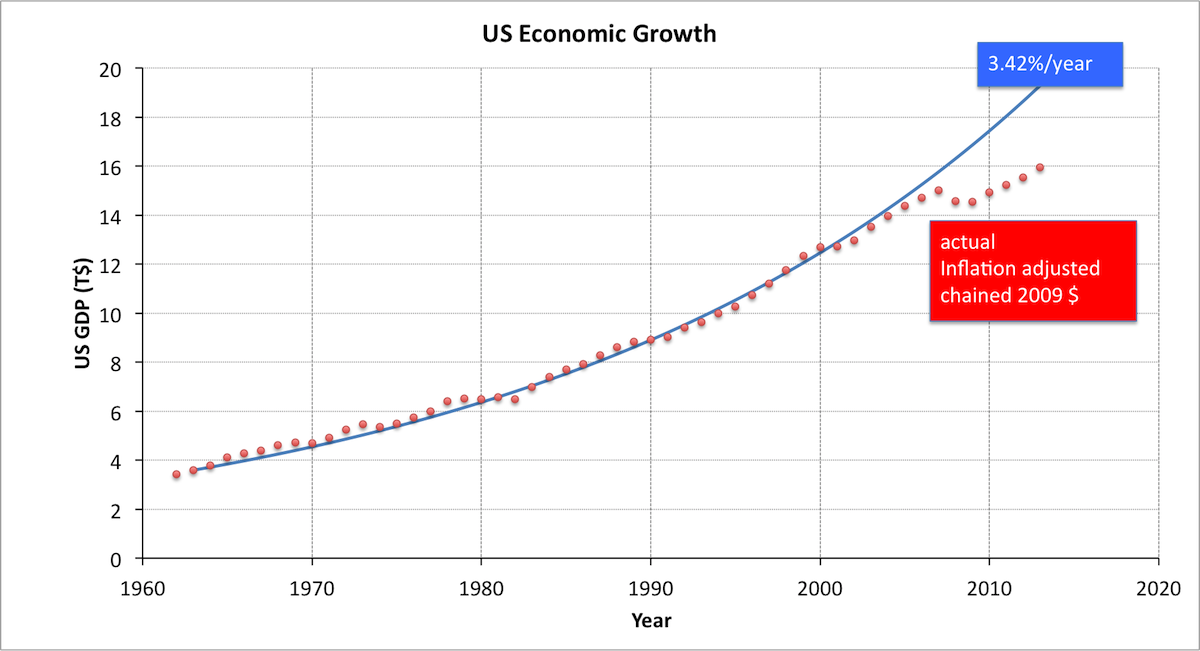

In the next graph, we show the United States gross domestic product, corrected for inflation into 2009 dollars, as red dots. The blue line is a very simple model for the data, which assumes a constant annual growth of 3.42% per year.

You can see that the blue line fits the measured data very precisely until 2007: that is, the US economy grew at a very constant 3.4% annual rate from 1963 to 2007. For those who enjoy statistics, the correlation coefficient between the measured data and this simple model, excluding 2007 through 2013, is 99.8%. That's pretty danged good even for the physical sciences. There is no evidence whatsoever for a sustained increase in growth some time after 1982, which would correspond to the hypothesis that patents benefit innovation and growth.

The data is even clearer when presented on a logarithmic scale. Logarithms are the numbers to which a base, such as 10, must be raised to produce a value. Thus, the logarithm of 10 is 1, the logarithm of 100 is 2, and so on. Logarithms have many virtues and are widely used in data analysis; see for example

Wikipedia:Logarithmic Scale

In this context, a constant growth rate becomes a straight line on a logarithmic plot. In the next graph, we can easily see that patenting growth has been a roughly constant 4.4% per year after about 1980.

The final image shows US GDP again plotted logarithmically.

It's readily apparent that the GDP data lies almost perfectly on the straight line of constant 3.4% annual growth, until the Great Recession. (And it's scarily clear that the slope of the line is now lower than it has been in the past five decades.) It's even easier to see that there is no correlation between patenting and GDP. We could double the system again, or get rid of it altogether, and expect no significant effect on overall prosperity in the United States. US patents do not play a measurable role in overall economic growth.

Now, it's worth noting that there is an abrupt decrease in GDP in the Great Recession of 2007, followed by what appears to be a secular decrease in sustained economic growth thereafter, to about 2.3% per year. It's hard even for the most dedicated opponent of the patent system to blame a sudden event in 2007 on a trend starting in 1981. But one could also argue that the sudden deflection in 2007-2008 must not be real, but must reflect a discrepancy between "real" economic growth and recorded GDP, so that growth may have slowed substantially earlier than shown. A possible version of this idea is depicted by the dotted green line, which illustrates the hypothesis that growth slowed to 2.3% per year around 1998, but the change was not observed by the means used to measure GDP until 2007. If we were to accept this hypothesis as real, we see the change in growth started in the late 90's, about 15 years after the change in the patent system - at the outer edge of plausible time delays. Even if US economic growth slowed a while ago, it's hard to claim the event was correlated with a change in the patent system occurring much earlier. We can't really assert that patents hurt the US economy, only that they don't help it. In the next post we'll establish a more dramatic correlation demonstrating the real effects of patent monopolies.

It's not impossible that this absence of utility is a consequence of the specific system we have used in the United States for the last few decades, and that another "better" system might show superior results. A similar examination of patents in other jurisdictions would be helpful, though it seems unlikely that other countries have made such nice dramatic changes in their policies in corresponding times. (I'd love to be wrong about that.)

In the next post we'll examine what patents are correlated with, and therefore what their real role in society probably is.

SOURCES:

USPTO, http://www.multpl.com/us-gdp-inflation-adjusted/table, http://democrats.judiciary.house.gov/sites/democrats.judiciary.house.gov/files/documents/Kappos131020_1.pdf

[Posted at 09/20/2014 01:36 PM by Daniel Dobkin on IP and Economics  comments(0)] comments(0)] [Posted at 01/10/2014 08:46 AM by Sheldon Richman on IP and Economics  comments(1)] comments(1)] A key quote from a fascinating article on photographer Annie Lebovitz and the artificially induced pricing within the world of photographic art found here:

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/76af3c7a-dbf2-11df-af09-00144feabdc0.html

[H/T: AndrewSullivan.com]

[Posted at 11/04/2010 02:53 PM by Justin Levine on IP and Economics  comments(0)] comments(0)] There are various ways to explain what is wrong with IP. You can explain that IP requires a state, and legislation, which are both necessarily illegitimate. You can point out that there is no proof that IP increases innovation, much less adds "net value" to society. You can note that IP grants rights in non-scarce things, which rights are necessarily enforced by physical force, against physical, scarce things, thus supplanting already-existing rights in scarce resources. (See, e.g., my Against Intellectual Property, " The Case Against IP: A Concise Guide" and other material here.)

Another way, I think, to see the error in treating information, ideas, patterns as ownable property is to consider IP in the context of the structure of human action. Mises explains in his wonderful book Ultimate Foundations of Economic Science that "To act means: to strive after ends, that is, to choose a goal and to resort to means in order to attain the goal sought." Or, as Pat Tinsley and I noted in "Causation and Aggression," "Action is an individual's intentional intervention in the physical world, via certain selected means, with the purpose of attaining a state of affairs that is preferable to the conditions that would prevail in the absence of the action."

Obviously, the means selected must therefore be causally efficacious if the desired end is to be attained. Thus, as Mises observes, if there were no causality, men "could not contrive any means for the attainment of any ends". Knowledge and information play a key role in action as well: it guides action. The actor is guided by his knowledge, information, and values when he selects his ends and his means. Bad information--say, reliance on a flawed physics hypothesis--leads to the selection of unsuitable means that do not attain the end sought; it leads to unsuccessful action, to loss. Or, as Mises puts it,

Action is purposive conduct. It is not simply behavior, but behavior begot by judgments of value, aiming at a definite end and guided by ideas concerning the suitability or unsuitability of definite means.

So. All action employs means; and all action is guided by knowledge and information. (See also Guido Hülsmann's " Knowledge, Judgment, and the Use of Property," p. 44.)

Causally efficacious means are real things in the world that help to change what would have been, to achieve the ends sought. Means are scarce resources. As Mises writes in Human Action, "Means are necessarily always limited, i.e., scarce with regard to the services for which man wants to use them."

To have successful action, then, one must have knowledge about causal laws to know which means to employ, and one must have the ability to employ the means suitable for the goal sought. The scarce resources employed as means need to be owned by the actor, because by their nature as scarce resources only one person may use them. Notice, however, that this is not true of the ideas, knowledge and information that guides the choice of means. The actor need not "own" such information, since he can use this information even if thousands of other people also use this information to guide their own actions. As Professor Hoppe has observed, " in order to have a thought you must have property rights over your body. That doesn't imply that you own your thoughts. The thoughts can be used by anybody who is capable of understanding them."

In other words, if some other person is using a given means, I am unable to use that means to accomplish my desired goal. But if some other person is also informed by the same ideas that I have, I am not hindered in acting. This is the reason why it makes no sense for there to be property rights in information.

Material progress is made over time in human society because information is not scarce and can be infinitely multiplied, learned, taught, and built on. The more patterns, recipes, causal laws that are known add to the stock of knowledge available to actors, and acts as a greater and greater wealth multiplier by allowing actors to engage in ever more efficient and productive action. (It is a good thing that ideas are infinitely reproducible, not a bad thing; there is no need to impose artificial scarcity on these things to make them more like scarce resources; see IP and Artificial Scarcity.) As I wrote in "Intellectual Property and Libertarianism":

This is not to deny the importance of knowledge, or creation and innovation. Action, in addition to employing scarce owned means, may also be informed by technical knowledge of causal laws or other practical information. To be sure, creation is an important means of increasing wealth. As Hoppe has observed, "One can acquire and increase wealth either through homesteading, production and contractual exchange, or by expropriating and exploiting homesteaders, producers, or contractual exchangers. There are no other ways." While production or creation may be a means of gaining "wealth," it is not an independent source of ownership or rights. Production is not the creation of new matter; it is the transformation of things from one form to another the transformation of things someone already owns, either the producer or someone else.

Granting property rights in scarce resources, but not in ideas, is precisely what is needed to permit successful action as well as societal progress and prosperity.

This analysis is a good example of the necessity of Austrian economics--in particular, praxeology--in legal and libertarian theorizing (as Tinsley and I also attempt to do in "Causation and Aggression"). To move forward, libertarian and legal theory must rest on a sound economic footing. We must supplant the confused "Law and Economics" movement with Law and Austrian Economics.

[Mises; SK] [Posted at 01/05/2010 11:10 PM by Stephan Kinsella on IP and Economics  comments(4)] comments(4)] [Posted at 01/05/2010 07:09 AM by Stephan Kinsella on IP and Economics  comments(1)] comments(1)] Someone recently told me "I just ran across a few of your interviews and writings. I was particularly impressed with the point that IP creates scarcity where none existed before. Despite its obviousness, it is characteristic of IP that had not occurred to me before."

So I thought I would elaborate a bit on this. The "artificial scarcity" insight is indeed a good one, but it is not mine. From pp. 33-34 of Against Intellectual Property:

Ideas are not naturally scarce. However, by recognizing a right in an ideal object, one creates scarcity where none existed before. As Arnold Plant explains:

It is a peculiarity of property rights in patents (and copyrights) that they do not arise out of the scarcity of the objects which become appropriated. They are not a consequence of scarcity. They are the deliberate creation of statute law, and, whereas in general the institution of private property makes for the preservation of scarce goods, tending . . . to lead us "to make the most of them," property rights in patents and copyrights make possible the creation of a scarcity of the products appropriated which could not otherwise be maintained.[64]

Bouckaert also argues that natural scarcity is what gives rise to the need for property rules, and that IP laws create an artificial, unjustifiable scarcity. As he notes:

Natural scarcity is that which follows from the relationship between man and nature. Scarcity is natural when it is possible to conceive of it before any human, institutional, contractual arrangement. Artificial scarcity, on the other hand, is the outcome of such arrangements. Artificial scarcity can hardly serve as a justification for the legal framework that causes that scarcity. Such an argument would be completely circular. On the contrary, artificial scarcity itself needs a justification.[65]

Thus, Bouckaert maintains that "only naturally scarce entities over which physical control is possible are candidates for" protection by real property rights.[66] For ideal objects, the only protection possible is that achievable through personal rights, i.e., contract (more on this below).

[64] Arnold Plant, "The Economic Theory Concerning Patents for Inventions," p. 36. Also Mises, Human Action, p. 364: "Such recipes are, as a rule, free goods as their ability to produce definite effects is unlimited. They can become economic goods only if they are monopolized and their use is restricted. Any price paid for the services rendered by a recipe is always a monopoly price. It is immaterial whether the restriction of a recipe's use is made possible by institutional conditions such as patents and copyright laws or by the fact that a formula is kept secret and other people fail to guess it." [For more on Mises's view of IP, see Mises on Intellectual Property.]

[65] Boudewijn Bouckaert, What Is Property? (text version) in "Symposium: Intellectual Property," Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy 13, no. 3 (Summer 1990), p. 793; see also pp. 797-99.

[66] Bouckaert, "What is Property?" pp. 799, 803.

Bouckaert's paper, What Is Property? (text version), is, by the way, superb and highly recommended.

Update: Jeff Tucker's article and recent speech had me thinking about something that ties into this post well. People want to impose artificial scarcity on non-scarce things because they think scarcity is good. But they have it backwards. If anything, we should want material things to be non-scarce.

In Tucker's talk, he was pointing out the difference between scarce resources and non-scarce, infinitely reproducible ones. Yes, they are different, but I think we also need to combat another fallacious view: people seem to implicitly think it's bad that ideas are infinitely reproducible. This is a "problem" we need to combat by making them artificially scarce. But it's a good thing.

i.e., at least ideas are non-scarce; but unfortunately, material things are scarce. But it would be good if material things were more abundant. So imagine that some benevolent genius invents a matter-copying device that lets you just point it at some distant object, and instantly duplicate it for free for you. So I see a coat you are wearing, click a button, and now I have an identical copy. I see you having a nice steak, and duplicate it. Etc. This would make us all infinitely wealthy. It would be great. Of course people would fear the "unemploymetn" it would cause--hey, I want to be unemployed and rich! And the rich would hate it because they would now not be special. They couldn't lord their Rolls Royces and diamonds over the poor; the poor would have all that (it would be similar to how audiophiles were irked by the advent of the CD so tried to find granite turntables etc. to pretend they were still better). So imagine a rich guy suing a guy who "copied" his car.... imagine farmers suing people who copied their crops to keep from starving... how absurd! And what damages would they ask for? Not monetary damages--the defendant could just print up wealth to pay him off! So the only remedy he could want would be to punish or impoversih the defendant... for satisfation, to once again feel superior. How sick.

As my friend Rob Wicks noted, you could imagine a short story based on this in which judge orders a famine as a remedy to crop-copying. [Posted at 12/03/2009 07:14 AM by Stephan Kinsella on IP and Economics  comments(2)] comments(2)] This subject will appear off-topic initially but bear with me. The Economist magazine has a long article, "Japan's technology champions," about the mid-sized highly specialized companies which dominate several manufacturing fields link here. The prime example is the world's sole maker of the huge forged pressure vessels for nuclear power plants. But there are a host of others that number among the top two or three firms in their industry. All share a characteristic attention to rigorous quality standards.

While computers, for example, have become commodities, certain components are highly technical and hard to make, like the substrate in the fabrication of chips. The article notes that for these firms, the "technology is tacit, not formal. It cannot be transmitted by writing a manual or reading a patent application. Rather it accumulates by working with colleagues over many years. This poses a barrier to entry for rivals."

Other features of these firms result, including their avoiding mergers based on the fact that the strength of the company lies in its current employees, their heavy spending on r & d, on keeping the core technology secret, on owning their supply chain, and even on manufacturing their own specialized tools.

Here again, we see that technical progress is not the result of patents or copyrights, but from the tradition of innovation that put these firms at the top of their industries. This is particularly important as economies pass from the copying and catch-up phases that we see in the emerging industrial states. The next stage is developing the innovative technical skills on which rising incomes in leading economies like the US will depend.

[Posted at 11/11/2009 09:42 AM by John Bennett on IP and Economics  comments(1)] comments(1)] [Posted at 10/27/2009 11:19 AM by Stephan Kinsella on IP and Economics  comments(3)] comments(3)]

|

|

|