Oooops, conceptual typo.

Aaaack, blew it again.

Third time's the charm:

There. Dull but relevant.

Peer review is the process of grabbing people who are familiar with a field to look at a paper or book before it gets published. It has been used in various forms for a long time in the sciences; Wikipedia provides a nifty history of the process. While 19th-century reviewers were often journal editors or staff, in the twentieth century reviewers were generally folks who had themselves published papers related to the one under consideration, the reviewers being recruited by journal editors. In the modern crowd-sourced world, journals are experimenting with open reviews, in which an article is published and then reviewed by whoever is interested, with the reviewers' comments becoming part of the publication.

A limited form of peer review, known as the Peer-to-Patent project, has already been tried by the US Patent Office. A first version ran in 2008, and a revised project ran from October 2010 to September 2011. Both were administered in cooperation with the New York Law School, and were limited to certain areas of art, including software-related patents, and later biotechnology, and speech recognition. Patents submitted to the program got earlier review as a reward. Smaller related projects have also been run in Australia and Japan. Most importantly, the reviewers were limited to submitting prior art they thought was related to the patent, and optionally annotating the art to help an examiner.

NYLS published a couple of anniversary reports (Peer to Patent home page). The program was also evaluated in some detail by students James Loiselle, Michael Lynch, and Michael Sherrerd at Worcester Polytechnic Institute ("Evaluation of the Peer to Patent Pilot Program"). While various administrative problems were encountered, even this limited program clearly contributed to the ability of examiners to access relevant prior art. At the very least, Peer-to-Patent ought to be revived and extended to all areas of art.

However, the process as it has so far been tried treats the public as servants assisting examiners but exercising no judgment. Peer review in the sciences may leave the final decision to an editor, but encourages reviewers to be full participants in the intellectual endeavor of evaluating the submitted work. As we described in the previous post, it is the focus on comparing claims to one or two prior publications, rather than actually reading and comprehending the specification, that gives rise to many of the absurd results we see from the patent system. In order to make peer review contribute fully to the patent process, we need to realize that people skilled in the relevant art are not just a theoretical legal construct but a reality, and ensure that they contribute (hopefully thoughtfully) to the process of examination. We therefore propose the following elaborated peer review process.

Every patent application should be subject to obligatory peer review to supplement the existing examination. The pool of reviewers may be administered by the USPTO, or administered by professional organizations relevant to specific arts (such as the IEEE for electrical and computer engineering) as representatives of the USPTO. To ensure an adequate pool of qualified reviewers, the USPTO should require that a person cannot file a patent application unless they have also registered to act as a reviewer. (This particular provision, at least, is likely to require legislation. I never said reform was easy.) An alternative, more stringent condition, would be that any would-be applicant must have performed at least (for example) three reviews of other people's applications in the previous year. The status of international applicants may be arranged through suitable agreements, such that they can fulfill the same duties as US citizens, while subject to the laws of their country of residence.

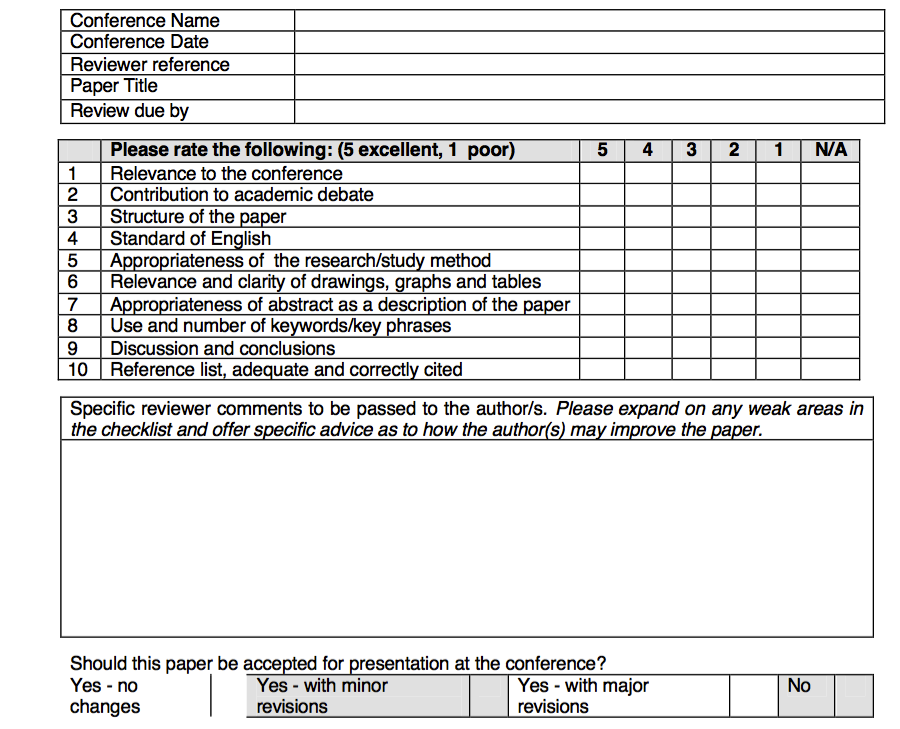

The reviewer should be bound to examine the specification and provide their best objective evaluation of:

• NOVELTY: whether a novel invention is described;

• ENABLEMENT: whether the invention is described in sufficient detail to allow them (or anyone else of ordinary skill) to practice the invention without undue experimentation;

• UTILITY: whether the described invention is useful to practitioners of the relevant art.

Reviewers may optionally express an opinion regarding claims submitted in the application. The examination process, as we have noted, already puts way too much emphasis on partitioning ownership; there's no need to add more.

It is an interesting question how reviewers for a specific application should be selected, since a reviewer ought to be conversant in the field of interest for the application. Since would-be applicants would be required to register as reviewers, it is possible to also require that they state the fields in which they are knowledgeable, and then have applications recommended by an examiner. The examiner may also look at past filings, or technical publications, by a reviewer to see what areas they work in. These approaches are analogous to peer reviewers selected by journal editors based on past publications. Self-selection is an alternative in the modern internet-based world, but might be usefully accompanied by a brief statement of why a reviewer is qualified to review a specific application, or perhaps a resumé.

Reviewers may cite prior art that they believe to be relevant, just as in the Peer-to-Patent program. As noted in the program evaluation, it is also important that they annotate the cited art to clarify what the examiner might want to look at.

Each review becomes a part of the file wrapper for the application. (That's the official record of the prosecution of a specific patent, and becomes publicly available after publication.) There is no requirement that an examiner take the reviews into account, except that s/he should look at any additional cited art. However, in the event of litigation related to a granted patent from the application, the unedited reviews must be entered as evidence and made available to the jury. Reviewers may be called but shall not be obligated to testify, except to provide an affadavit ensuring that the cited reviews were in fact produced by them.

Note the fact that an applicant MUST be a reviewer addresses the issue of ensuring that patents are indeed reviewed, a concern in the earlier projects. The requirement of review as a precondition for filing also addresses any reticence an employer might have in allowing an employee to review; if they want to file, they have to allow their employees to review.

Disclosure of a patented invention is the price of monopoly. The strange idea that an application should be secret should never have arisen and should be abandoned in any case; it should not be an obstacle to review. Review by people who know what they are reading will help ensure that the invention is actually comprehensively and comprehensibly disclosed. It will help reduce the tendency of applicants to intentionally file before they know how to enable an invention, thus avoiding effective disclosure while securing monopoly rights.

The question of anonymity of reviewers, and of applicants, is a continual challenge and a subject of experimentation in the sciences; there is no reason we should expect the best answer to be immediately apparent for a patent review system. However, in the case of patents, I suggest that there are strong arguments for disclosure and attendant responsibilities. In order to qualify to hold monopolies, a would-be applicant must review. In order to ensure that he or she does so responsibly, they should NOT be anonymous. Disclosure also makes it possible to review qualifications and expose conflicts of interest that might taint their review.

I have proposed that reviewers are not exposed to testimony in litigation, except to confirm that the review in question was in fact produced by them and has not been tampered with, but a good case could be made that reviewers should provide testimony in litigation (presumably being compensated in doing so just as any hired experts are). I can assure the readers, from personal experience, that testifying in civil litigation sucks, at least for people with ethical standards. If this makes people reluctant to review patents, it will then reduce the number of people who can file, which -- if patents are unhelpful to the overall economy, as we previously showed -- could be a good thing.

BENEFITS AND CHALLENGES:

The great benefit of requiring a record of critical reviews is that, when litigation occurs, a possibly objective examination of the virtues of the patent or patents in use will exist -- something that doesn't happen otherwise. Incomprehensible specifications, specs that don't describe anything useful, or merely contain all the things that any skilled person would try, will be described as such by someone who (we hope) doesn't have a direct interest in the litigation. Ideas that are actually new and important will also get the benefit of such characterization. Peer review, properly conducted, will help create a background understanding of whether something new and useful was usefully disclosed, against which the arguments about what is owned and what is not can take place.

The program as proposed will create a professional obligation for people who wish to be able to file patent applications. There's nothing bad about tying privileges to obligations. If it is administered by professional societies, those societies will benefit, and thus become supporters of the program. If it administered by the USPTO, it will need to be funded, always a challenge.

Naturally, as with any system, people will try to cheat and manipulate the results. Peer review in the sciences has encountered many challenges and has experienced some spectacular failures. We can't expect this to be any easier.

While some of what is outlined above can be accomplished by the USPTO (or equivalent organizations) on their own authority, requirements limiting the ability to file will certainly require legislation, obviously a major challenge in the modern world. International filers will also need to be treated fairly, requiring revisions to existing international agreements, again time-consuming and laborious.

And that's the easy proposal. But if you don't start, you can't finish. More to come.