In the claimless view of the patent world, a patent differs from the prior art in that the instructions for making the patented object contain, amongst all the known combinations of what has gone before, a new combination of prior-art stuff that did not previously exist. It's important to understand that all supposed inventions are combinations of the prior art. No one invents from scratch. Therefore, in measuring the distance between the prior art and the new object, we need to measure the new combination and not count the prior-art part of it.

To clarify how such a measure might work, let's build some block buildings. Readers may remember wooden blocks from their own childhood, or have more recent vicarious experience by way of their children, or other kids they know. Most kids go through a set of increasingly elaborate steps to build better block buildings. The steps are something like:

1. Pile a block on top of another one:

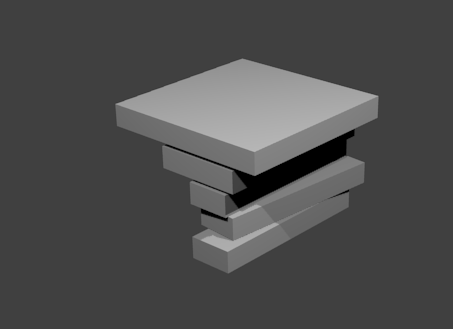

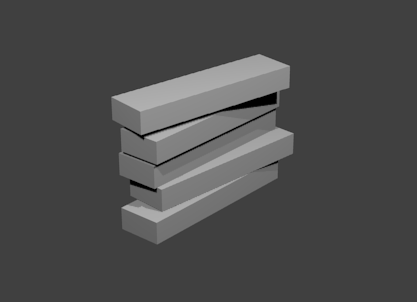

2. Pile a bunch of blocks on top (that is, iterate step 1):

3. Choose the upper blocks to be the same size as the first one, or smaller:

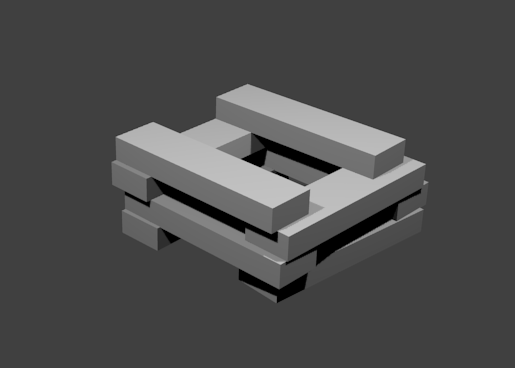

4. Make four piles in a rectangle to make a building with walls (we'll skip the roof for now):

5. Interpenetrate the sidewalls to make a stronger building:

Let's look at a putative patent for concept number 5. The instructions are:

• put down two blocks of the same size, in parallel (prior art)

• space the blocks less than one block length apart (new instruction)

• finish the rectangle with two blocks perpendicular to the first two but lying on top of the first two (new instruction)

• iterate to make the building taller (prior art)

If a person of ordinary skill in the block building art is a kid about age 4, another kid can instruct them in the inventive step by showing them how to move the first two blocks close together. The action is actually quite complex - ask anyone who has to make a robot do it - but from the point of view of the typical block-builder-of-ordinary-skill, it's two instructions. Once you show the kid the interpenetrating part, he or she can make a whole building the new way.

Remember that each elementary action here rests on a complex series of prior art instructions. Someone got the rights to cut down a tree (which they hopefully replace in order to provide for future kids), someone did the cutting and transport, others ran machines that sliced the wood into block-sized pieces, smoothed the surfaces, optionally painted or stained the wood, and still others packaged the results, established distribution channels, and added marketing materials to appeal to kids and thus obligate their parents to purchase the result. A kid doesn't have to worry about this complex infrastructure, but it's all there. We don't count that infrastructure as part of the invention of interpenetrating walls. We don't count the step of placing the layers of blocks parallel to one another, or the ability to measure spacing relative to block size - the good block builder knows these things. We don't count piling the blocks up to make the building taller (iteration) - again, a block building kid knows how to do this. The interpenetrating wall block building differs by two elementary instructions from the solid wall block building. The Hamming distance from the prior art is 2. And that's a verifiable statement: you find a kid who likes to build block buildings, but doesn't do interpenetrating ones, and show them. Is demonstration of the new steps enumerated above sufficient for them to proceed? If yes, we've properly captured the steps needed.

Notice also that we aren't arguing whether the kid would discover interpenetrated buildings for herself - that is, we don't care if it's obvious or profound (as if we could tell!), just if it's different from what has been done so far. Inventiveness is measured by how far the new thing is from the prior art - how many new things I need to tell you so you can practice what I preach.

In the next post, we'll try applying this procedure to a typical US patent (specifically US 8,698,473). You can read ahead if you want.

*If you've been reading the previous posts in this series, you knew that terrible pun was inevitable -- just a matter of time.